Unravelling the Drug Pricing Blame Game

Analyzing the factors influencing prescription drug costs at U.S. retail pharmacies

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, few healthcare issues received as much attention and public discourse as prescription drug prices. The attention paid to the costs of pharmaceuticals is understandable when one considers that, in many ways, medicines are arguably the backbone of the U.S. healthcare delivery system. Whether a person is seeking treatment for a simple infection or complex diseases like cancer or multiple sclerosis, prescription drugs are the primary tools employed by our nation’s healthcare professionals to address illness. Moreover, prescription drugs are often the goal of researchers who are looking to offer solutions for medical conditions without current treatments. However, informed debate over drug prices is challenging because the nature of drug prices requires layers of context. That said, the common understanding of the American public appears to be that the pricing practices of drug manufacturers are primarily to blame for high drug costs. While there is certainly truth to the notion that drug manufacturers are key contributors to the prices paid for medicines, our study of 32.6 million retail pharmacy claims from independent, small chain, and mid-size chain pharmacies over a 12-month period between January 1, 2020 and December 31, 2020 finds that a great deal more context is needed to understand drug prices at the pharmacy counter.

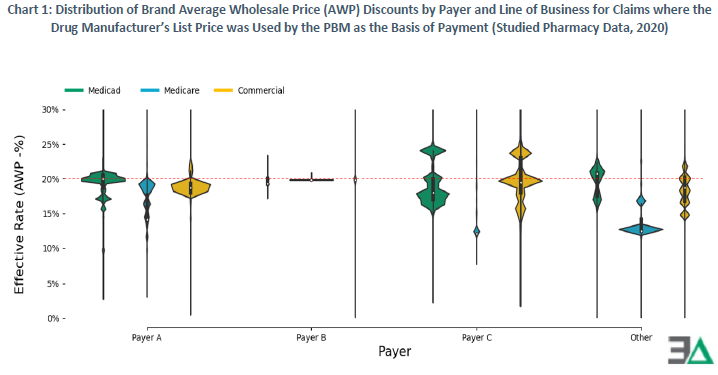

More specifically, in our analysis, we find that the overwhelming majority of the prices paid at the pharmacy counter are based on price points established by the drug supply chain intermediaries known as pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs). For expensive brand medications, the data demonstrates that PBMs establish variable payment rates based upon differentiating the discounts offered to manufacturer price points (Chart 1 below).

Digging deeper, we observed how a brand medication (Eliquis), with one established manufacturer price point for 2020, can have a variety of pharmacy counter prices, irrespective of its unchanging list price and even when controlling for the PBM setting the drug discount (Chart 2 below).

For generic medications, the most routinely utilized of all drug therapies, we observed that proprietary PBM prices (i.e., maximum allowable cost, or MAC) were used for setting the majority of all prescription costs and that like their brand counterparts, generic drug prices were highly variable and disconnected from the manufacturer or pharmacy established price for the medication. For example, we identified that within the claims where pharmacies lost and made the most money (i.e., margin), the same national drug codes (NDCs) were present in both extremes 44.6% of the time – meaning that the same drug could be responsible for both the highest profits and the biggest losses for pharmacies (Chart 3 below).

If pharmacies are to make drug acquisition and purchasing decisions based on the incentives of drug reimbursement (the purported rationale for generic drug pricing), it is difficult to rationalize what incentive actually exists when the majority of claims appear just as likely to result in favorable reimbursement as will result in unfavorable reimbursement.

Our study found that the greatest harm from our system’s current approach to drug pricing appears to be on patients. Though variability in drug prices appears greatest on generic drugs, patients are sharing in more of these drug costs relative to brands (Chart 4 below). This observation signals that patients are at greatest risks of directly experiencing the extreme ends of drug pricing variability.

Our findings confirm that, for at least a subset of drugs, claim costs are higher when patients and health plans are sharing drug costs rather than when health plans alone are responsible for drug costs. (Chart 5 below).

Ultimately, we observe that the drug prices experienced at the pharmacy counter in 2020 were set in highly inconsistent and irregular ways. Within this report, we repeatedly observed drugs with known low acquisition costs, such as duloxetine, having multiple (and highly varied) price points – price points that cannot be readily attributed to either the drug manufacturer or the pharmacy provider. The most extreme example of this was a single pharmacy who, on a single day, for the same product (on an NDC basis), at the same quantity, was paid five unique prices by the same PBM, ranging from $9.30 per prescription to $96 per prescription (Chart 6 below).

On this day, there was only one acquisition cost for this NDC by the pharmacy (as represented by NADAC). Similarly, on this same day, there was only one set of manufacturer-established price points (as represented by WAC and/or AWP). No system predicated on manufacturer prices, and manufacturer prices alone, could produce the results in Chart 6. The result of this system design exposed patients and health plans to drug prices at the pharmacy counter that were up to a 10-fold difference despite the same pharmacy, dispensing the same drug, on the same day, to patients covered by the same PBM. Furthermore, we cannot readily explain what was accomplished through these kinds of drug price-setting disparities and inequity.

While these disparate pricing experiences can have a significant impact on pharmacy providers and health plan sponsors, the most obvious and important impact is felt by the patient, whose costs for their medicines are often derived by the point-of-sale prices that are yielded by their health benefits plan and PBM.

Ultimately, the findings in this study underscore the complexity, inconsistency, and malleable nature of drug pricing in the United States, where public policy goals for reform are scattered but loosely centered on a quest for affordability and value. With this in mind, this report demonstrates that the current system is full of inequity and misaligned incentives that would seem to run counter to these goals. Addressing the current system dysfunction that exposes many to inflated, varied, and frankly, unfounded drug prices appears to be as rational of an approach as any other potential policy goal for reforming the U.S. drug distribution system.

We hope that the insights contained in this report can build upon previous net drug pricing research and help to better shorten the bridge between understanding and misunderstanding the cost drivers within the prescription drug supply chain.

We could not have devoted even a fraction of the time spent on this project had it not been for the financial support of the American Pharmacy Cooperative, Inc (APCI). We are immensely grateful for organizations like APCI, as if it were not for them, there would be little resources available for exploratory research and analysis of the U.S. prescription drug supply chain.